Since I retired, I decided to view films I’ve never seen before (and have always meant to) as well as movies I haven’t viewed in ages.

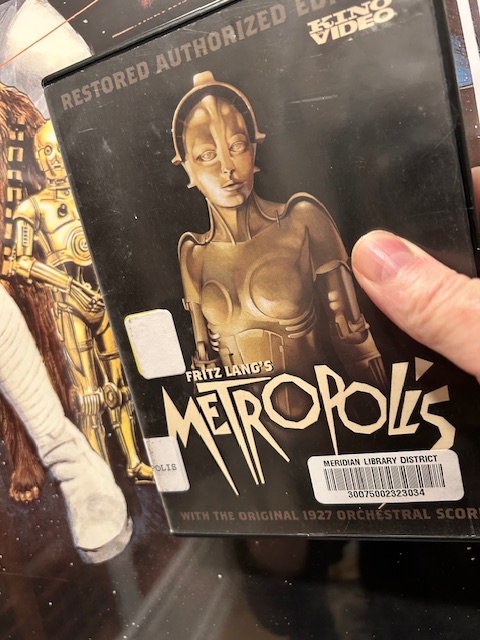

Last night, for the first time, I saw Fritz Lang’s Metropolis (1927). I haven’t watched a silent film in a very long time, but I’d taken enough film classes in my youth that I’m perfectly fine with the experience.

That said, you don’t watch this movie unless you’re a serious science fiction fan or a film student. Film making has changed a lot in the past century and the acting and makeup in early cinema borrowed heavily from the stage. In other words, the actors looked like they had plaster on their faces and their acting (by modern standards) was melodramatic.

I was saddened to learn that about a quarter of the original film was lost. There’s a long history of the efforts in attempting to restore this masterpiece, but what is gone is gone.

The story is set in 2026 (imagine that) in a technological utopia, all shining cities, bright lights and wonder. Lang conceived of the overall “sweep” of the movie when visiting New York City a few years before making this film.

However, the real work in maintaining the city is performed in the depths by the grueling manual labor of pitiful human workers (the early 20th century hadn’t conceived of automation yet).

It’s the classic trope of the haves and have nots. Our protagonist is Freder (Gustav Fröhlich), the son of the city’s leader and head architect of Metropolis Joh Fredersen (Alfred Abel). He’s frolicking with a bunch of young ladies in a garden when Maria (Brigitte Helm) brings a bunch of worker children (much against the rules) to see what their “brothers” and “sisters” up top look like.

She’s shooed away but Freder is fascinated with her. He follows her down to the machine levels and sees the pain and suffering required to keep him in the proverbial lap of luxury. An accident kills scores of workers and he’s horrified.

The movie makes use of a great deal of Biblical imagery including the pagan god Moloch who is depicted as the machine to which thousands of humans are bodily sacrificed. Maria is shown as a Christian saint and Freder encounters monks who quote various Bible passages about the apocalypse. Maria herself tells the tale of the Tower of Babel, which, like Metropolis, is conceived by privleged minds but built on the backs of slaves.

Fredersen’s nemesis and ally is the mad inventor Rotwang (Rudolf Klein-Rogge) who has lost a hand (see Darth Vader and Luke Skywalker) in creating his greatest machine, a robotic “Machine-Man” (also played by Helm in a robot suit). Both Rotwang and Fredersen loved the same woman Hel, but she married Fredersen and died giving birth to Freder. Rotwang’s bitterness and sense of loss made him attempt to recreate her in a soulless being.

Learning of Maria’s plot to unite the workers and her prediction of a mediator that will bridge the gap between them and the elites, Fredersen orders Rotwang to give the robot (the word is never used in the film, see this for more) Maria’s face (whole body, actually) and use her to prompt the workers to violently revolt. He’ll then have the excuse to put down the riot with violence and break their will.

Rotwang kidnaps Maria and uses her form to duplicate her in the machine. While the machine is inciting the workers to riot and also enticing the upper-class men in the city with her dancing, all symbolizing her role as the Biblical “Whore of Babylon,” the real Maria is Rotwang’s prisoner.

But Rotwang has betrayed Fredersen and plans to use the workers to completely destroy Metropolis as revenge for depriving him of Hel.

In the meantime, Freder has taken the place of a worker (number 11811 played by Erwin Biswanger) and saved the life of one of his father’s dishonored minions (Theodor Loos as Josaphat) who remain loyal to him and finally save his life when robot Maria turns the workers into a mob which attacks them.

The rioting workers do their job too well and the destruction of the machines causes a flood that nearly drowns all their children. An escaped Maria along with Freder and Josaphat, save them.

When the workers realize this, they blame the “witch” Maria, eventually capturing her (after mistaking the real Maria for her) and burning her at the stake. She turns back into a robot before her demise, shocking poor Freder.

Much heroic action takes place, Maria is saved, and Rotwang is destroyed. Fredersen repents but it takes Freder, the predicted mediator, to bring his father and and the workers together.

Happy ending.

This is a German film, and although Lang was Jewish, it turns out “Metropolis” was one of Adolf Hitler’s favorite films.

From the IMDb trivia on this movie:

Much to Fritz Lang’s dismay, Adolf Hitler and Joseph Goebbels were big fans of the film. Goebbels met with Lang and told him that he could be made an honorary Aryan despite his Jewish background. Goebbels told him “Mr. Lang, we decide who is Jewish and who is not.” Lang left for Paris that very night.

And…

The connection of this film to the Nazi regime is quite remarkable. Thea von Harbou, who was Fritz Lang’s wife, was an ardent and early supporter of the party. Not only Adolf Hitler, but all the inner circle were entranced by the film and considered it as a sort of social blueprint. Lang, of course, was Jewish but the Fuehrer offered him a pass for his ingenuity and vision, very rare in Nazi Germany. He fled to Paris, then eventually America.

Given the current political turmoil in America, I can imagine many people will see parallels.

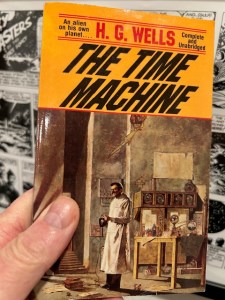

Interestingly enough, H.G. Wells hated the movie and totally panned it in his review. I guess he preferred his 1895 novella on a similar theme, The Time Machine.

The real importance for science fiction fans in the current age is the influence “Metropolis” had on later works such as:

Flash Gordon (Ming’s palace, especially). 1984 (1984). Frank Lloyd Wright. Star Trek. Star Wars. I, Robot. Ringo Starr’s Goodnight, Vienna album cover, and so many others. -IMDb trivia

I’m glad I watched it, though I wouldn’t recommend “Metropolis” for a bit of light entertainment on a Friday night. It’s good to know where modern science fiction came from and like so many other things, you can’t really appreciate what you have now unless you study what was before it.